- Код статьи

- S013216250014371-1-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S013216250014371-1

- Тип публикации

- Статья

- Статус публикации

- Опубликовано

- Авторы

- Том/ Выпуск

- Том / Номер 2

- Страницы

- 177-188

- Аннотация

The paper examines the specifics of the perceptions on inequalities by the Russian middle class on the eve of the crisis of 2020. The empirical analysis is based on the data subarray from the International Social Research Program. The middle class was defined in the tradition of multidimensional stratification according to the criteria of socio-professional status, education, and income level. It is shown that the middle class shares a common understanding of the system of inequalities that characterizes modern Russian society with other groups of the population. The existing inequalities are assessed by middle class, as by Russians in general, as excessively deep and illegitimate. The role of the key actor in combating inequalities is assigned to the government, but its actions in relation to their reduction are seen as insufficient and ineffective. It is shown that middle class representatives consider themselves to be representatives of the “middle”, not upper strata. In this regard, when discussing inequality, they mean not a gap between their position and the position of other mass population groups, but a significant and growing gap between the very small elite and all other Russians, to whom they belong. This fact is reflected in the specifics of the perceptions of the social conflicts as seen by the population, the key of which they currently consider to be the conflict between the poor and the rich. Dissatisfaction with the lack of action on the part of the state in regard to inequalities from the middle class, which concentrates the most educated, qualified, and independent Russians, becomes an important challenge that raises the question of the social contract revision.

- Ключевые слова

- middle class, inequalities, income inequality, social structure, public opinion, attitudes, perception of inequality

- Дата публикации

- 21.04.2021

- Год выхода

- 2021

- Всего подписок

- 6

- Всего просмотров

- 223

Theoretical and methodological context of the study of the middle class perceptions about the social structure Interest in the middle class both in Russian sociology and among the general public is developing in waves. In certain historical periods, there were sharp bursts of it, when in the presence of a mass middle class and the characteristics of its representatives, they began to look for indicators of the success of reforms, a social base to support a new course of development of the country, the prerequisites for the formation of demand for changes or, conversely, a guarantee of social stability1. At other times, middle class issues disappeared from the agenda, replaced by the problems of poverty and inequality. Another, albeit short-term, surge of interest in the middle class occurred in March 2020 in connection with the statement by Vladimir Putin that its share in the Russian society was 70%. However, the unfolding of the economic downturn under the influence of the coronavirus pandemic and the dynamics of oil prices quickly shifted the focus of attention from the middle class to issues of the expected dynamics of poverty in the new conditions.

Discussions about the middle class in Russian science, as a rule, come to various approaches to identifying it and assessing the objective characteristics of its representatives – share among population, composition, features of the economic situation, employment situation, etc.2 The study of the subjective characteristics of representatives of the middle class, in particular, the specifics of their perceptions about the social structure, is also of considerable interest. However, in Russian sociology, this aspect is traditionally paid less attention, with some exceptions3.

3. Mareeva S. Middle Class: system of values and perceptions on country’s development vector // Journal of Economic Sociology. 2015. Vol. 3. No. 1. P. 39–54; Gorshkov M.K., Tikhonova N.E. (Eds.). Srednii klass v sovremennoi Rossii. Opyt mnogoletnikh issledovanii [The middle class in modern Russia. The experience of long term research]. Moskva, 2016. (in Russ.).

While there is a fierce debate in Russian sociological literature about whether the term “middle class” can be used at all, in the Western tradition the subjective characteristics of the middle class are one of the important areas of analysis. The attitudes and value orientations of the middle class are often viewed in terms of their political preferences. One of the roles traditionally assigned to the middle class is being the “bastion of democracy”4, and its formation as a mass and stable social entity in countries undergoing a period of transformation is considered an important prerequisite for democratization5. On the other hand, a number of studies argue that the support for democracy by the middle class is by no means universal – for example, the Chinese middle class, the structure of which is noticeably shifted towards the public sector of the economy (which also characterizes the Russian middle class), turns out to be less oriented towards democratic values than other strata, while in a number of Latin American countries, it was the middle class that provided social support for authoritarian regimes in the 1970s6. In Russia, issues about the role of the middle class as a political entity have been in the focus of attention for some time after the social protests of 2011–20137; however, the lack of uniform criteria for its identification created different opinions on whether the middle class was the main actor of protest actions.

5. Diamond L. The Spirit of Democracy. New York, 2008; Gontmakher E., Ross C. The middle class and democratisation in Russia // Europe-Asia Studies. 2015. Vol. 67. No. 2. P. 269–284.

6. Chen J. A Middle Class without Democracy. Oxford, 2013.

7. Volkov D. The protest movement in Russia 2011–2013: Sources, dynamics and structures // Ross, C. (Ed.), Systemic and Non-Systemic Opposition in the Russian Federation: Civil Society Awakens. Ashgate, 2015. P. 35–50; Rosenfeld B. Reevaluating the middle-class protest paradigm: A Case-control study of democratic protest coalitions in Russia // American Political Science Review. 2017. Vol. 111. No. 4. P. 637–652.

In this paper, the authors would like to turn to the perceptions of the middle class in connection with the system of inequalities that characterize modern Russian society. Without getting involved in any methodological disputes on different approaches to identification of the middle class, the authors proceed from the fact that the assessment of the social structure by the most qualified and educated Russians needs special attention, since it they can act as a key mass actor in a new model of national sustainable development based on human capital as its main factor – through the choice of relevant behavioral practices and strategies at the individual level. However, to realize this potential, the vector of national development at the macro level has to correspond to their preferences and demands at the micro level. The specifics of their perception of the system of inequalities that have developed in the country can determine their request for the state and act as a resource or a constraint for the sustainable socio-economic development8. This is especially important in the current turbulent socio-economic situation, when the trajectory of the country's exit from the crisis largely depends on the behavior of the population. Therefore, it is important to assess whether there is a value gap with respect to estimates of inequality between different population groups.

The empirical basis for this study was the subarray of data from the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) for Russia. The survey was conducted in January 2019, its sample consisted of 1,626 respondents over 18 and represented the country’s population by federal districts, settlements with different numbers of residents, education levels, as well as gender and age.

Methodology for identifying the middle class The theoretical and methodological foundations for identifying the middle class is a separate academic issue, the solution of which is primarily associated with the choice of an approach to its analysis (economic, sociological, subjective), each of which is effective in solving particular problems9. In this case, the authors use the neo-Weberian approach, the most common in Russian studies10, defining the middle class on the basis of multidimensional stratification according to three criteria: socio-professional status: white collars, with the exception of trade and service workers (classes 0 to 4 as per the International Standard Classification of Occupations for those who are currently employes, or were employed in relevant positions at the latest job); level of education: higher, including incomplete higher education for those who, at the time of the survey, continued their studies at the university; income level: median income by type of settlement and higher.

10. Maleeva T.M. (Ed.). Srednie klassy v Rossii: Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye strategii [Middle Classes in Russia: Economic and Social Strategies]. Moskva, 2003. (in Russ.); Gorshkov M.K., Tikhonova N.E. (Eds.). Srednii klass v sovremennoi Rossii. Opyt mnogoletnikh issledovanii [The middle class in modern Russia. The experience of long term research]. Moskva, 2016. (in Russ.); Tikhonova N.E. Srednii klass v fokuse ekonomicheskogo i sotsiologicheskogo podkhodov: granitsy i vnutrenniaia struktura (na primere Rossii) [Middle class in the focus of various theoretical approaches: thresholds and internal structure (on the example of Russia)] // Mir Rossii [Universe of Russia]. 2020. Vol. 29. No. 4. P. 34–56. (in Russ.); Pishniak A.I. Dinamika chislennosti i mobil'nost' srednego klassa v Rossii v 2000–2017 gg. [The population dynamics and mobility of the middle class in Russia, 2000–2017] // Mir Rossii [Universe of Russia]. 2020. Vol. 29. No. 4. P. 57–84. (in Russ.)

Fulfillment of all three criteria simultaneously allows to identify those Russians who can receive (or received prior to termination of work) the rents on their human capital, sufficient to at least maintain the level of their human capital as the main asset. Calculations based on ISSP data showed that the share of the core of the middle class, for which all three of these criteria are simultaneously fulfilled, amounts to 11.4% of the population. Another 23.5% of Russians are characterized by the presence of two of the three characteristics, and in the concentric model of social structure, they can be considered the periphery of the middle class core. With this methodological approach to identifying the middle class, the majority of Russians have no more than one attribute – hereinafter this group is called “the rest of the Russians”, implying that its representatives do not have the potential to become part of the middle class.

The middle class defined in this way is characterized by the specificity of its socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics, which influence, among other things, its attitudes and values. However, in this case, the task is not to single out the effects of individual factors, but, on the contrary, to identify how the concentration of various class characteristics (simultaneous positions in the hierarchies of education, socio-professional status, and income) determines the specifics of the middle class as a special social entity that shares particular ideas about the social structure and is different (or not) in this respect from the rest of the population. Status inconsistency that characterize the position of middle strata representatives in modern Russian society [Kolennikova, 2019], emphasizes the relevance of a relevant analysis for a group that is characterized by the consistency of its representatives’ positions in key hierarchies, albeit its share among population is not large.

Middle class perceptions of social structure and inequalities in modern Russia The data show that the assessment of the existing income inequality in Russia not only as excessively deep, but at the same time as extremely unfair, is typical today for all strata of the population without exception. There is no value split in this respect – the middle class does not stand out against the background of other social groups either in its greater tolerance or in its more critical attitude. More than 90% of representatives of all social groups, including the core of the middle class, assess monetary inequality in modern Russian society in this way (Table 1).

Table 1 Perceptions of income inequality in different social groups, % agreed

|

Statements |

Core of the middle class | Periphery of the middle class | Rest of Russians |

| Differences in incomes in Russia are too large | 94.0 | 94.5 | 90.4 |

| The existing income distribution is rather unfair/very unfair | 91.8 | 94.7 | 94.7 |

| The government should reduce the gap between rich and poor | 91.7 | 93.1 | 92.3 |

| Most politicians in Russia do not care about reducing income inequalities | 89.0 | 87.0 | 84.0 |

| The government is rather unsuccessful/totally unsuccessful at present in reducing income disparities | 74.9 | 85.8 | 81.9 |

At the same time, the role of the key actor in the fight against inequality is assigned by Russians to the state; however, the assessment of its real actions in this regard is very critical (Table 1) – the overwhelming majority of representatives of all selected classes believe that the state should reduce income disparities between different income groups, but most politicians do not care about this, and the government’s actions in this regard can be described as unsuccessful. In the core of the middle class, the failure of the state’s actions is mentioned a little less often, but even in this group, there are almost three-quarters of those who agree with that.

According to the “tunnel effect” model proposed by Hirschman, the possibilities of upward social mobility (even without affecting individuals personally) increase the population’s tolerance to inequalities in general11. However, in the context of individual social groups and the current situation in Russia, this effect is not observed – at least in the context of the monetary dimension of inequality. The positions of representatives of the middle class in the income hierarchy are more favorable than those of the representatives of other groups; they also differ in the dynamics of their positions. In particular, the middle class more often experiences upward integral mobility – assessing their positions on a ten-point scale five years ago and at the time of the survey, in 2019, 21.6% of the middle class representatives noted a rise – along with only about 15% in other social groups. Speaking about income alone, then over the past three years, more than a third of the middle class representatives (35.1%) have managed to improve their financial situation, with 22.3% of the periphery and 17.6% of the rest of the population. However, despite this, the attitude towards monetary inequalities that characterize modern Russian society as excessively high and unjust, unites the middle class and the rest of the population rather than separates them.

How can one explain such a unity of the population in this respect? When speaking about inequality in Russian society and the gap between the rich and the poor, the representatives of the middle class, most likely, do not mean income differences among the mass strata of the population – that is, between themselves and other, less prosperous groups. For them, the point is about a significant and not decreasing separation of a small and very prosperous elite (3–5% of the population, not included in the mass polls), from the rest of the population, to which they self-refer. It is difficult to obtain accurate quantitative estimates of such a gap, since the most well-to-do population groups are not included in mass surveys, and the methods for re-evaluating their incomes based on data on taxes, inheritance, Forbes lists, and other sources are based on a number of assumptions, differences in which lead to noticeable discrepancies in the respective estimates. However, even taking into account these discrepancies, the results of different research teams, based on data from various sources, agree that Russia is one of the world leaders in terms of the concentration of both current income and accumulated wealth in the hands of the top of the population, especially 1% or even smaller subgroups in its composition12. Moreover, the “explosive” income growth in the post-Soviet period of the country’s development is characteristic of the absolute minority of the population (Table 2). This situation, which characterizes the structure of Russian society as a model with a very thin “spire” going up endlessly, is perceived by the entire population, including representatives of the middle class, as unfair and requiring active intervention from the state.

Table 2 Income dynamics in Russia, 1989 to 2016, % (data from Novokmet et al., 2017, Appendix B, Table 2)

| Income group | Average annual real income growth rate | Cumulative (total) real income growth rate for the period |

| All population | 1.30% | 41% |

| Lower 50% | -0.80% | -20% |

| Middle 40% | 0.50% | 15% |

| Top 10% | 3.80% | 171% |

| Including 1% | 6.40% | 429% |

| Including 0.1% | 9.50% | 1,054% |

| Including 0.01% | 12.20% | 2,134% |

| Including 0.001% | 14.90% | 4,122% |

At the same time, speaking about attitudes towards inequalities in the mass strata of the population, it should be noted that representatives of both the middle class and the less well-off classes accept their certain depth. The Russians who fall into the core of the middle class are most tolerant of their depth. Thus, representatives of all the identified classes agree on estimates that an unskilled factory worker should be paid 30,000 rubles/month13, and a similar level of wages is seen by Russians as fair for a shop assistant. At the same time, a fair salary for a qualified specialist with higher education – for example, a general practitioner – is already estimated by Russians at 50,000 rubles. Thus, the middle class, like the rest of the population, undoubtedly accepts wage differentiation due to differences in structural positions in the labor market in terms of the level of education and qualifications they require). Assessing the real situation, representatives of the middle class, like other classes, believe that the work of mass professions in the modern Russian economy is systematically underpaid, and this applies to a greater extent to highly qualified specialists – i.e. to positions typical of the middle class itselfНЕ. For example, representatives of the middle class assess the real level of wages of a general practitioner in 30,000 rubles, and of shop assistants and unskilled workers – in 20,000 rubles.

Speaking about the remuneration of the groups that make up the “top”, which was discussed above – for example, ministers in the Russian government or CEOs of large corporations, the people, including the middle class, believe that in reality, they recieve much more than they should. Apparently, it is to such groups that the feeling of the unfairness of their incomes, which creates the deepest inequality between them and the rest of the population, as noted above, first of all belongs. Thus, the population estimates on average the real wages of ministers at the level of 500,000 rubles, considering that the level of 100,000 rubles would be fair (except for representatives of the middle class, who consider a higher level of payment to be fair – 150,000 rubles). The population estimates the real level of remuneration for a CEO of a large corporation in the range of 500,000-1,000,000 rubles, the fair level being 100,000-200,000; the highest indicators of a fair level of remuneration are again characteristic of the middle class. It is clear that the realities of life of these groups are far from those of a typical representative of the middle class – however, such assessments, based on normative ideas about income inequality, clearly demonstrate “stress points”. Thus, representatives of all classes of Russian society – both prosperous and not – agree that unskilled and skilled mass labor in Russia is underestimated, while the work of top-level managers is overestimated, although representatives of the middle class core in this regard allow for the possibility of higher pay and, accordingly, higher income inequalities in society as a whole.

In assessments of one of the most important tools of state policy to reduce income inequality – the tax system, both actually operating in the country today and perceived as being fair, representatives of the middle class again express attitudes typical for the entire population (Table 4). Thus, more than two-thirds of the middle class agree that taxes for those who have high incomes are low today (71.9% versus 70.2% for the entire sample), and only every 6.2% representatives of the middle class consider them high (with 8.8% among the general population). Speaking about the preferred taxation system, the overwhelming majority support a progressive scale, with more than half voting for a significant difference in the level of tax rates paid from income (from 58.8% among the middle class to 62.0% among the rest of Russians).

Table 3 Ideas about tax policy aimed at income equalization, % agreed

|

Statements |

Core of the middle class | Periphery of the middle class | Rest of Russians |

| People with high incomes must pay a significantly higher tax rate than those with low incomes | 58.8 | 58.5 | 62.0 |

| Taxes in Russia for those with high incomes are low or too low | 71.9 | 72.9 | 68.9 |

Such data make it possible to confirm the above assumption that the representatives of the middle class, having a higher level of current income and occupying objectively higher positions in the general structure of modern Russian society as compared to other Russians, do not associate themselves with those rich whose positions lead to deep and unfair inequalities.

This can also be seen from self-assessments of their positions in society – they identify themselves, first of all, with the middle stratum. Thus, 68.3% of the core of the middle class and 45.9% of the periphery, with only one-third of the rest of Russians, consider themselves to be representatives of this stratum, while only 4.8%, 2.4 %, and 0.9%, respectively, identify themselves with the upper part of the middle stratum, and identification with the upper stratum is not typical of either the middle class or Russians as a whole.

The fact that Russians from the middle class consider themselves “typical” representatives of society, and not a prosperous subgroup of it, is also confirmed by their assessments of their position on the “social ladder” of 10 steps, where 1 is a low position and 10 is a high one. The average scores of the middle class on this scale are 5.66 points, while those of other groups are slightly below 5 points. On the whole, this characterizes the subjective model of the stratification of modern Russian society as “shifted downward”; within its framework, representatives of the middle class are characterized by median assessments of their position, while representatives of the other two classes are characterized by lower than average assessments.

In this case, it is not surprising that when assessing the social conflicts existing in Russian society between various groups, the population considers the conflict between the poor and the rich to be the most acute. Again, this is typical for all social groups: for example, hostility between the poor and the rich is considered very strong or strong by 70.1% of the middle class, 69.9% of its periphery, and 62.0% of other Russians. Judging by the self-assessments by the middle class of their positions in society, as discussed above, speaking about this hostility, they also assess the “social rift” not between themselves and other mass strata of the population, but between the mass population as a whole, to which they self-refer, and the “top” being far away from it. It should be noted that against this background, other possible lines of social conflict as assessed by both the middle class and other groups of the population are much less noticeable: for example, the hostility between the employers and employees is assessed as strong or very strong by only 41.3% of the middle class, between those born in Russia and those who migrated to the country – by 34.4%, between young people and the elderly – by 19.5%, respectively.

Separately, it is necessary to dwell on the perception by the population of the class conflict – the confrontation between the working class and the middle class. This conflict is also not at all actualized today in the minds of Russians, including its potential “parties”: for example, only 23.2% of the middle class see hostility between these classes, and only 5.4% consider it very strong. This traditional measure of class inequality does not seem to be a painful point for either the middle class or Russians from other social groups – in contrast to the acutely perceived confrontation between the massively poor and the rich, which demonstrates the sharpness of monetary inequality in modern Russia, and testifies to the perception of the very “top” as a special class opposed to the rest of the Russians.

It is worth saying a few words about the attitude of representatives of different classes that has developed in these conditions towards the key non-monetary manifestations of income inequality – differentiated access to health care and education among people with different incomes. In this respect, Russians from the core of the middle class demonstrate somewhat greater tolerance than representatives of other groups. Perhaps this is due to the fact that, as previous studies have shown, they are the most active consumers of paid educational and medical services, and not because of free alternatives missing, i.e. forcedly, but due to the rational choice of the best quality alternatives to any available free opportunities14. This is caused not only by the availability of such material opportunities, but also by their values and attitudes that form an understanding of the importance of investment in human capital15. However, even in the core of the middle class, more than half share the view that access to better health care services and better education for children, which is open to people with high incomes, is unfair (Table 4).

15. Mareeva S.V. Praktiki investirovaniia srednego klassa v svoi chelovecheskii kapital [Practices of middle class investment in their human capital] // Terra Economicus. 2012. Vol. 10. No. 1. P. 165–173. (in Russ.)

Table 4 Assessment of inequalities in different population groups, %

|

Statements |

Core of the middle class | Periphery of the middle class | Rest of Russians |

| It is unfair that high-income people can benefit from better health care services than low-income people | 53.9 | 57.0 | 62.8 |

| It is unfair that high-income people can give their children a better education than low-income people | 59.9 | 60.8 | 66.6 |

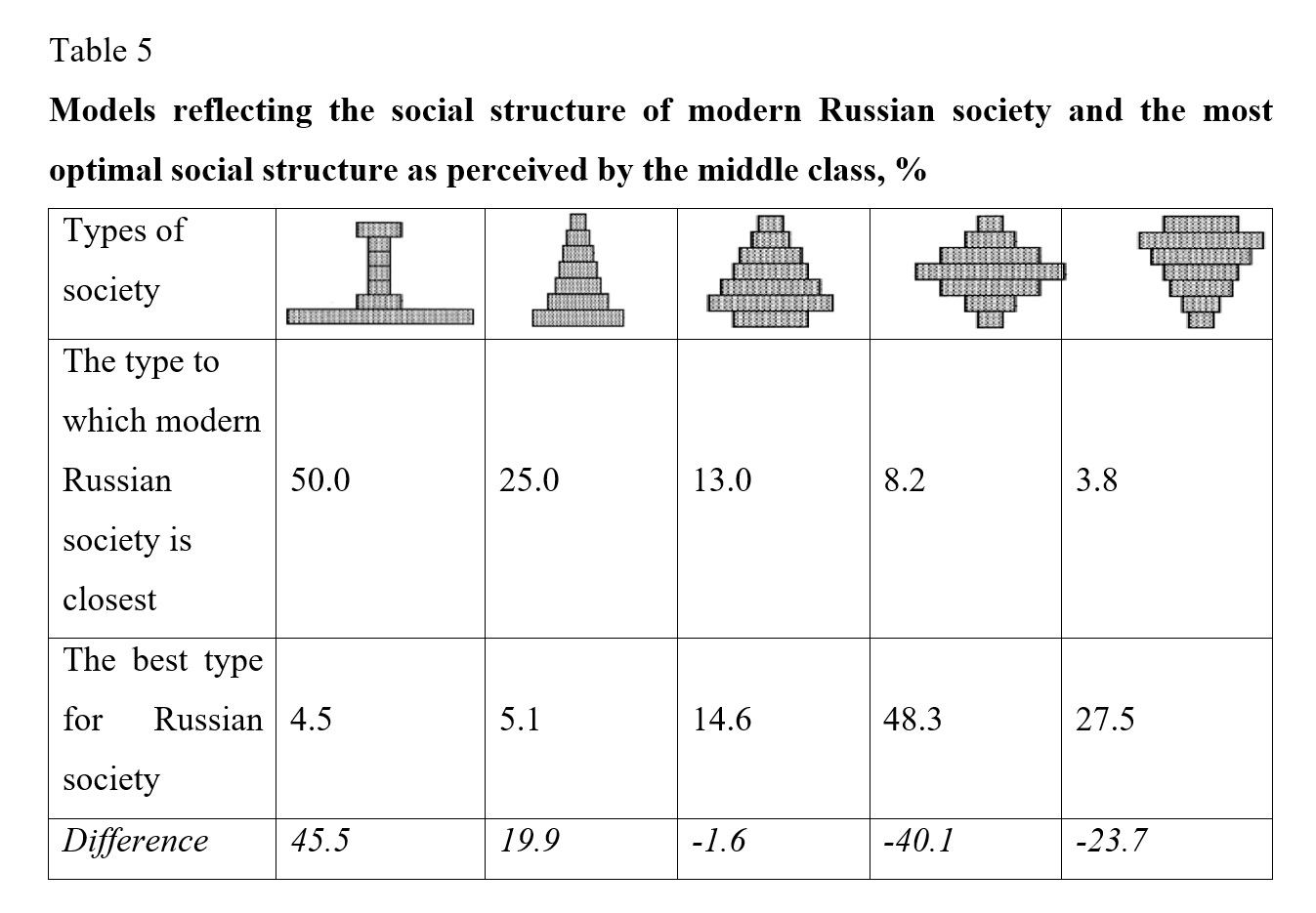

Finally, the integral attitude of representatives of various social groups towards inequalities in modern Russia can be traced in their choice of the models of the social structure of society, which they consider to characterize real Russian society, on the one hand, and most suitable for it, on the other. In this respect, despite some quantitative differences, the representatives of the middle class are again more likely to be in solidarity with other Russians (Table 5). While the real structure of society appears to them as a model with a small elite at the top and the bulk of the population at the bottom, they would like to see the society of the mass middle strata as the ideal structure. This contradiction also determines the specificity of attitudes towards inequalities that representatives of the middle class demonstrate – even despite their more prosperous position in society and the upward social mobility characteristic of some of their representatives.

Above, we have focused on the characteristics of the middle class perception of the social structure, showing that in this respect it, by and large, does not differ from the rest of the mass population. It may seem that this is due to the specific country specificity of the Russian middle class – for example, general passivity or general similarity with other strata of the population. However, this is not at all the case. In particular, numerous empirical studies show that the middle class, identified within the tradition of multidimensional stratification according to the key criteria of education and socio-professional status, significantly differs from other groups of the population in a number of parameters. Among them, in particular, the modernized, activist nature of the values that Russians from the middle class are guided by in everyday life (orientation towards individualism, initiative, internal locus control), the widespread use of active socio-economic strategies in the labor market, the high prevalence of investments in various types of resources – human, social, cultural16. Thus, at the level of actions taken in own life and related norms and attitudes, the middle class is distinguished by greater independence, activity, and readiness to independently solve problems. However, if one speaks about its attitudes regarding the situation with the social structure of the country as a whole, the situation is different – in this respect, it shares the opinion of the entire population.

Middle-class perceptions of social inequalities: implications and challenges for the state. The results of this analysis show that from the point of view of normative ideas about the structure of modern Russia, especially in terms of socio-economic inequalities that characterize a pre-crisis situation, the middle class is in solidarity with the rest of the population, demonstrating universal ideas for Russians about the excessive depth of inequalities, the key role of the state in reducing them in the normative model and the lack of effectiveness of the related practices in reality. Although the middle class is distinguished by the features of strata identity and self-assessments of their position in society, its representatives assess themselves as representatives of the “middle,” and by no means the “prosperous” strata of society. This also explains the consensus opinion of the middle class with other Russians that inequalities in society are too high – speaking of them, they mean not a gap between their position and that of the lower class, but the separation of a very small elite from the rest of the population, to which they belong. In other words, one cannot speak about a wide “value palette”17 with regard to the population’s perception of the social structure in the aspect of the system of inequalities that characterizes it. This is reflected in the specifics of the perception of social conflicts in modern Russian society by people, the key of which they consider to be the conflict between the poor and the rich, while the rest of them, including the class conflict between the middle and the working classes, are not actualized in the public consciousness and in the minds of the middle class representatives per se.

This gap between Russians’ perceptions of how society should function and their experiences with how social mechanisms and institutions actually operate is a source of social tension. The middle class, like other strata of the population, places the responsibility for establishing these “rules of the game” on the state. This is a consequence of the existing specific model of relations between the state and society, which is characteristic of neoethacratic societies18, in which the interests of the state prevail over the interests of the individual, and the state acts as a mediator between various groups, coordinating their interests with each other. Recent studies show, however, that this model is beginning to enter the stage of decomposition – by 2018, the focus on the priority of the interests of the state in relation to the rights of the individual for the first time ceased to dominate in the public consciousness19. In this context, the growing dissatisfaction of all strata of the population without exception, including the middle class, with the lack of action on the part of the state, demonstrating at least the political will to solve key socio-economic problems, in particular, the problem of inequality, is becoming an important challenge that raises the issue of revising the social contract between society and the state.

19. Tikhonova N.E. Sootnoshenie interesov gosudarstva i prav cheloveka v glazakh rossiian: empiricheskii analiz [Correlation between the interests of the state and human rights in the eyes of Russians: an empirical analysis] // Polis. Politicheskie issledovaniia. 2018. No. 5. P. 134–149. (in Russ.)

Moreover, this channel of the formation of social tension – associated not with one’s position, but with normative ideas about the model of society – can have a greater influence on the specifics of the population’s request to the state in relation to its desired role in the economic and social spheres of life, or, more broadly, a certain configuration of the social contract. This is because such a request is based on the general normative principles of interaction between the individuals, society, and the state, while the request for specific assistance from the state depends to a greater extent on the particular situation, which is determined by the confluence of specific life circumstances20. In this regard, the position of the middle class is especially important, since its relatively more prosperous position in society determines its greater independence and a lower demand for direct participation and assistance of the state in solving certain problems in the lives of its representatives. At the same time, its role as a social actor that can promote or hinder the effective implementation of the sustainable development model is very great, which acknowledges the need to look for a balance point between the interests of the middle class and the state.

Библиография

- 1. Anikin V.A. Prekarizatsiia srednego klassa v novoi Rossii: o chem govoriat rezul'taty issledovaniia geterogennykh sloev? [Precarization of the middle class in the new Russia: what do the results of the study of heterogeneous strata show?] // Sotsiologicheskaia nauka i sotsial'naia praktika [Sociological Science and Social Practice]. 2019. No. 4. P. 39–54. (in Russ.)

- 2. Anikin V.A., Lezhnina Ju.P., Mareeva S.V., Slobodenjuk E.D. Kto i pochemu ishchet gosudarstvennoi podderzhki v novoi Rossii? [Who and why is seeking state support in the new Russia?] // Mir Rossii [Universe of Russia]. 2020. Vol. 29. No. 1. P. 31–52. (in Russ.)

- 3. Avraamova E.M., Maleva T.M. Evoliutsiia rossiiskogo srednego klassa: missii i metodologiia [The evolution of Russian middle class: missions and methodology]. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost' [Social Sciences and Contemporary World]. 2014. No. 4. P. 5–17 (in Russ.)

- 4. Gorshkov M.K., Tikhonova N.E. (Eds.). Srednii klass v sovremennoi Rossii. Opyt mnogoletnikh issledovanii [The middle class in modern Russia. The experience of long-term research]. Moskva, 2016. (in Russ.)

- 5. Grigor'ev L.M., Salmina A.A. Srednii klass v Rossii: povestka dnia dlia strukturirovannogo analiza [Middle class in Russia: an agenda for structured analysis] // Spero. 2010. No. 12. P. 105–124 (in Russ.)

- 6. Maleeva T.M. (Ed.). Srednie klassy v Rossii: Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye strategii [Middle Classes in Russia: Economic and Social Strategies]. Moskva, 2003. (in Russ.)

- 7. Maleva T.M., Burdiak A.Ia., Tyndik A.O. Srednie klassy na razlichnykh etapakh zhiznennogo puti [Middle classes at different stages of their life cycle] // Zhurnal Novoi ekonomicheskoi assotsiatsii [Journal of the New Economic Association]. 2015. No. 3(27). P. 109–138. (in Russ.)

- 8. Mareeva S.V. Praktiki investirovaniia srednego klassa v svoi chelovecheskii kapital [Practices of middle class investment in their human capital] // Terra Economicus. 2012. Vol. 10. No. 1. P. 165–173. (in Russ.)

- 9. Mareeva S.V. Sotsial'nye neravenstva i sotsial'naia struktura sovremennoi Rossii v vospriiatii naseleniia [Social inequalities and the social structure of modern Russia as perceived by the population] // Vestnik Instituta sotsiologii [Bulletin of the Institute of Sociology]. 2018. No. 3(26). P. 101–120. (in Russ.)

- 10. Mareeva S.V. Tsennostnaia palitra sovremennogo rossiiskogo obshchestva [Values in modern Russian society] // Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniia: ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny [Public Opinion Monitoring: Economic and Social Changes]. 2015. No. 4. P. 50–65. (in Russ.)

- 11. Mareeva S.V., Slobodenyuk E.D. Neravenstvo v Rossii v mezhdunarodnom kontekste: dokhody, bogatstvo, vozmozhnosti [Inequality in Russia in international context: income, wealth, opportunities] // Vestnik obshchestvennogo mneniia. Dannye. Analiz. Diskussii [The Russian Public Opinion Herald. Data. Analysis. Discussions]. 2018. No. 126 (1–2). P. 30–46. (in Russ.)

- 12. Ovcharova L.N., Popova D.O. Dokhody i raskhody rossiiskikh domashnikh khoziaistv: chto izmenilos' v massovom standarte potrebleniia [Income and expenses of Russian households: what has changed in the mass standard of consumption] // Mir Rossii [Universe of Russia]. 2013. Vol. 22. No. 3. P. 3–34. (in Russ.)

- 13. Petukhov V.V. Tsennostnaia palitra sovremennogo rossiiskogo obshchestva: "ideologicheskaia kasha" ili poisk novykh smyslov? [The value palette of modern Russian society: "ideological mess" or the search for new meanings?] // Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniia: ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny [Public Opinion Monitoring: Economic and Social Changes]. 2011. No. 1(101). P. 6–23. (in Russ.)

- 14. Pishniak A.I. Dinamika chislennosti i mobil'nost' srednego klassa v Rossii v 2000–2017 gg. [The population dynamics and mobility of the middle class in Russia, 2000–2017] // Mir Rossii [Universe of Russia]. 2020. Vol. 29. No. 4. P. 57–84. (in Russ.)

- 15. Shkaratan O.I. Gosudarstvennaia sotsial'naia politika i polozhenie srednikh sloev v sovremennoi Rossii [State social policy and the position of the middle strata in modern Russia] // Sotsiologicheskii zhurnal [Sociological Journal]. 2004. No. 1–2. (in Russ.)

- 16. Shkaratan O.I. Sotsial'naia sistema, obrashchennaia v proshloe (Chast' 2) [A social system facing the past (Part 2)] // Sotsiologicheskii zhurnal [Sociological Journal]. 2015. No. 4. P. 80–119 (in Russ.)

- 17. Tikhonova N.E. Osobennosti normativno-tsennostnoi sistemy rossiiskogo obshchestva cherez prizmu teorii modernizatsii [Features of the normative-value system of Russian society through the prism of modernization theory] // Terra Economicus. 2011. Vol. 9. No. 2. P. 60–85. (in Russ.)

- 18. Tikhonova N.E. Sootnoshenie interesov gosudarstva i prav cheloveka v glazakh rossiian: empiricheskii analiz [Correlation between the interests of the state and human rights in the eyes of Russians: an empirical analysis] // Polis. Politicheskie issledovaniia. 2018. No. 5. P. 134–149. (in Russ.)

- 19. Tikhonova N.E. Srednii klass v fokuse ekonomicheskogo i sotsiologicheskogo podkhodov: granitsy i vnutrenniaia struktura (na primere Rossii) [Middle class in the focus of various theoretical approaches: thresholds and internal structure (on the example of Russia)] // Mir Rossii [Universe of Russia]. 2020. Vol. 29. No. 4. P. 34–56. (in Russ.)

- 20. Tikhonova N.E., Mareeva S.V. Srednii klass: teoriia i real'nost' [Middle Class: Theory and Reality]. Moskva, 2009. (in Russ.)

- 21. Zaslavskaia T.I., Gromova R.G. K voprosu o "srednem klasse" rossiiskogo obshchestva [On the question of the "middle class" of Russian society] // Mir Rossii [Universe of Russia]. 1998. No. 4. P. 5–22. (in Russ.)

- 22. Abercrombie N., Urry J. (1983). Capital, Labour, and the Middle Classes. London, 1983.

- 23. Alvaredo F., Chancel L., Piketty T., Saez E., Zucman G. World Inequality Report 2018. Executive Summary. World Inequality Lab, 2018.

- 24. Chen J. A Middle Class without Democracy. Oxford, 2013.

- 25. Credit Suisse. Global Wealth Report. Credit Suisse Group AG, 2019.

- 26. Diamond L. The Spirit of Democracy. New York, 2008.

- 27. Gontmakher E., Ross C. The middle class and democratisation in Russia // Europe-Asia Studies. 2015. Vol. 67. No. 2. P. 269–284.

- 28. Hirschman, A.O., Rothschild, M. The Changing Tolerance for Income Inequality in the Course of Economic Development // The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1987. Vol. 87. No. 4. P. 544–566.

- 29. Lipset S. Some social requisites of democracy: economic development and political legitimacy // American Political Science Review. 1959. Vol. 53. No. 1. P. 69–105.

- 30. Mareeva S. Middle Class: system of values and perceptions on country’s development vector // Journal of Economic Sociology. 2015. Vol. 3. No. 1. P. 39–54.

- 31. Mareeva S., Ross C. The political values of the state and private sectors of the Russian middle class // Demokratizatsiya. 2020. No. 3 (in print).

- 32. Mareeva S.V. Middle class formation in Russia // Farazmand A. (Ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Cham, 2018.

- 33. Moore B. Jr. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. London, 1966.

- 34. Novokmet F., Piketty T., Zucman, G. From Soviets to Oligarchs: Inequality and Property in Russia, 1905–2016. No. W23712. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017.

- 35. Rosenfeld B. Reevaluating the middle-class protest paradigm: A Case-control study of democratic protest coalitions in Russia // American Political Science Review. 2017. Vol. 111. No. 4. P. 637–652.

- 36. Volkov D. The protest movement in Russia 2011–2013: Sources, dynamics and structures // Ross, C. (Ed.), Systemic and Non-Systemic Opposition in the Russian Federation: Civil Society Awakens. Ashgate, 2015. P. 35–50.